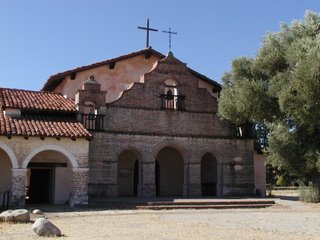

... you absolutely have to visit this mission if you can. Because unlike most of the California missions, this one is a time machine.

This is Mission San Antonio de Padua, in the remote hills of central California, maybe 100 miles south of San Jose. The Spanish missions were connected by a road called El Camino Real (i.e. The Royal Road), and today's Highway 101 -- one of the main north-south routes in the state -- usually follows its path. So most of the missions are right along the busy interstate, or surrounded by the towns that grew up around most of them. Well restored in most cases, but when you're there you have no doubt you're still in the 21st century.

Not San Antonio. It's in the middle of nowhere, because when Hwy. 101 was laid out, it took a different, easier route, about 15 miles farther inland. To get there, you take Jolon Road from near King City, which follows the old route of El Camino, winding past a few lonely ranches and seeing very very few other cars. It's a beautiful, quiet drive.

The mission is all the more isolated because it's on the grounds of Fort Hunter Liggett, an Army training base which is mostly just open, untouched land. So to actually get to it, you have to show your driver's license, registration, and insurance card to the courteous but obviously armed guard at the gate, who takes those things, goes back into his hut and (I sure hope) makes certain you haven't been sending money to Hezbollah lately, and then comes back with your pass.

The base headquarters disappears behind you, and a little farther down the road, you come to the mission. You pull up in front, switch off the ignition, get out and shut the door. And then you hear it:

Nothing.

Not a sound of the modern world. Probably not another visitor, either. Just you and the padres' pride and joy, baking there in the afternoon sun with that glorious California summer scent of hot dry grass and oaks and evergreens. Look around you, and all you'll see is the same golden brown hills they saw. You'll have a sense of the immense sacrifice they made to come to this wilderness and bring the Faith with them.

Close your eyes just a little, and it's 1780.

If there's a caretaker, he's not in evidence, yet everything is wide open, reminiscent of those days, only yesterday, when pretty much everyone left their doors unlocked.

You might wander into the dim and peaceful sanctuary:

or maybe pause at this luminous side chapel:

but when you leave, you'll know you've been in not just another place, but in a little private hidden corner where another time is still there to be savored.